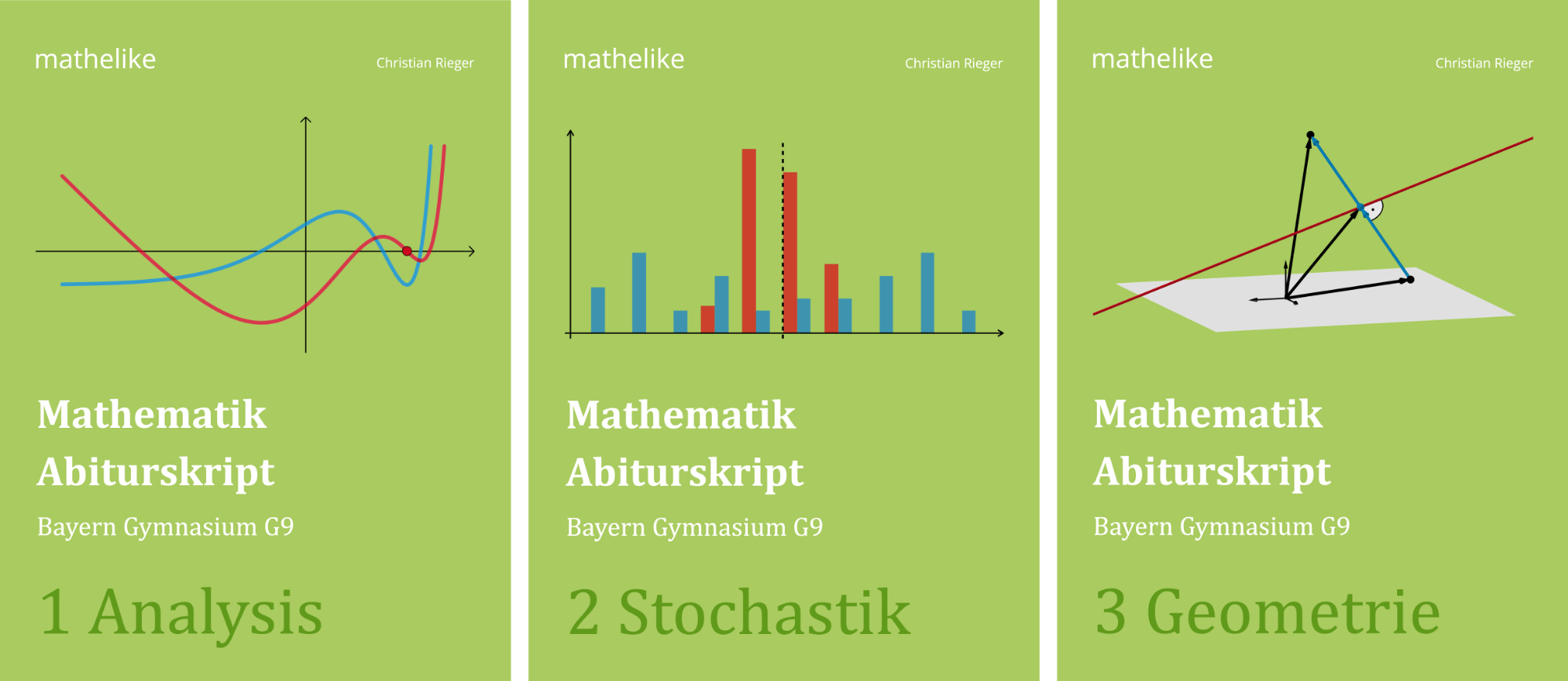

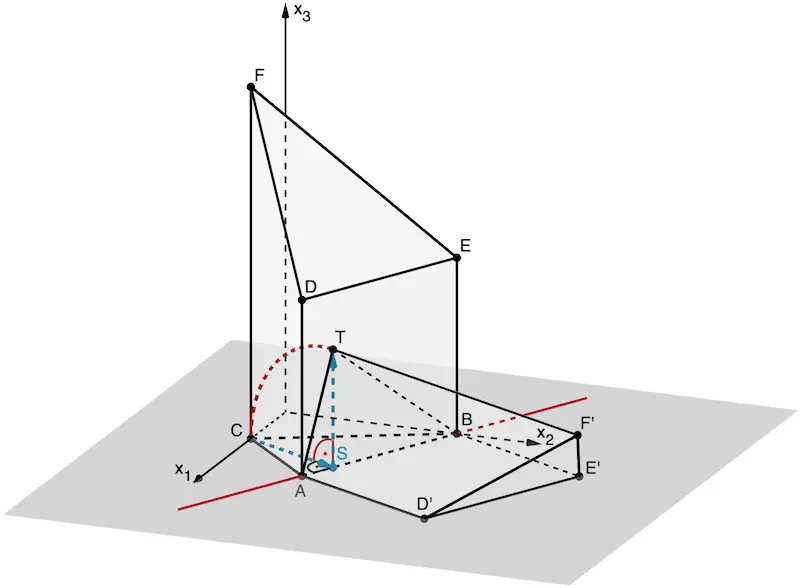

Der Körper wird so um die Gerade \(AB\) gedreht, dass der mit \(D\) bezeichnete Eckpunkt nach der Drehung in der \(x_1x_2\)-Ebene liegt und dabei eine positive \(x_2\)-Koordinate hat. Die folgenden Rechnungen liefern die Lösung einer Aufgabe im Zusammenhang mit der Drehung:

\(\begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \circ \left[ \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} - \begin{pmatrix} 3 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \right] = 0 \; \Leftrightarrow \; \lambda = 0{,}8\), d. h. \(S(4{,}8|3{,}6|0)\)

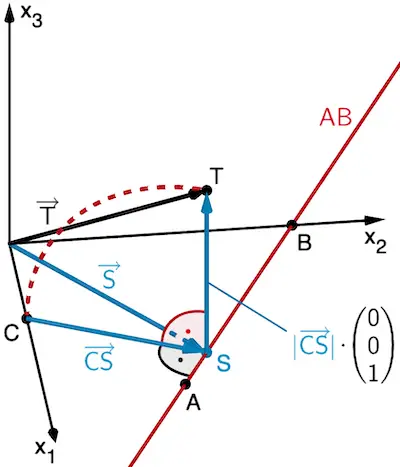

\(\overrightarrow{T} = \overrightarrow{S} + \vert \overrightarrow{CS} \vert \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\)

Formulieren Sie eine passende Aufgabenstellung und geben Sie die Bedeutung von \(S\) an.

(3 BE)

Lösung zu Teilaufgabe g

Mögliche passende Aufgabenstellung:

Der Eckpunkt \(C\) des Körpers \(ABCDEF\) wird nach der Drehung mit \(T\) bezeichnet. Bestimmen Sie die Koordinaten von \(T\).

oder

Der Punkt \(T\) entsteht aus dem Punkt \(C\) durch Drehung des Körpers \(ABCDEF\) um 90° um die Gerade \(AB\). Bestimmen Sie die Koordinaten von \(T\).

Bedeutung von \(S\):

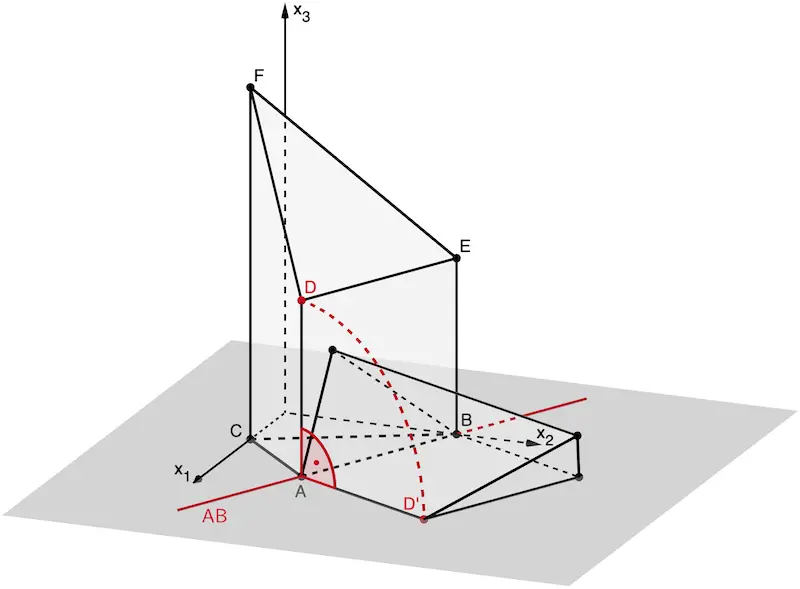

Der Punkt \(S\) ist Lotfußpunkt des Lotes von Punkt \(C\) auf die Gerade \(AB\).

Ausführliche Erklärung (nicht verlangt)

Die Aufgabenbeschreibung entspricht einer Drehung des Körpers \(ABCDEF\) um 90° um die Gerade \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}\).

Erster Teil der Rechnung

Die Gleichung

\(\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}_{\Large{\text{Vektor}}} \circ\underbrace{\left[ \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} - \begin{pmatrix} 3 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \right]}_{\Large{\text{Vektor}}} = 0\)

formuliert ein Skalarprodukt zweier Vektoren, das gleich null ist.

Die beiden Vektoren sind somit zueinander senkrecht.

Anwendung des Skalarprodukts:

Orthogonale (zueinander senkrechte) Vektoren (vgl. Merkhilfe)

\[\overrightarrow{a} \perp \overrightarrow{b} \; \Leftrightarrow \; \overrightarrow{a} \circ \overrightarrow{b} \quad (\overrightarrow{a} \neq \overrightarrow{0},\; \overrightarrow{b} \neq \overrightarrow{0})\]

\[\underbrace{\underbrace{\textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}}_{\Large{\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{BA}}}} \circ \underbrace{\left[ \smash{\underbrace{\textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}}_{\Large{\textcolor{#0087c1}{S}\, \in\, \textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}}}} - \smash{\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 3 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}_{\Large{\overrightarrow{C}}}} \vphantom{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}} \right] \vphantom{\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 3 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}_{\Large{\overrightarrow{C}}}}}_{\Large{\textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{CS}}}} = 0}_{\Large{\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{BA}}\, \circ\, \textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{CS}}\, =\, 0\;\Leftrightarrow\;\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{BA}}\,\perp\,\textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{CS}}}}\]

Planskizze empfohlen

Planskizze empfohlen

Der erste Vektor \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}\) ist der Verbindungsvektor \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{BA}}\), denn mit \(A(6|3|0)\) und \(B(0|6|0)\) gilt:

\[\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{BA}} = \overrightarrow{A} - \overrightarrow{B} = \begin{pmatrix} 6\\3\\0 \end{pmatrix} - \begin{pmatrix}0\\6\\0 \end{pmatrix} = \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 6\\-3\\0 \end{pmatrix}}\]

Der zweite Vektor \(\left[\textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}} - \begin{pmatrix} 3 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \right]\) ist ein Verbindungsvektor von Punkt \(C(3|0|0)\) zu einem Punkt auf der Gerade \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}\).

Denn mit \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{B(0|6|0)}\) als Aufpunkt und \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\overrightarrow{BA} = \begin{pmatrix} 6\\-3\\0 \end{pmatrix}}\) als Richtungsvektor, beschreibt \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}\) eine Parameterform der Gleichung der Gerade \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}\).

Gleichung einer Gerade / Strecke in Parameterform

Jede Gerade \(g\) kann durch eine Gleichung in der sogenannten Parameterform

\(g \colon \overrightarrow{X} = \overrightarrow{A} + \lambda \cdot \overrightarrow{u} \enspace\) mit dem Parameter \(\lambda \in \mathbb R\) beschrieben werden.

Dabei ist \(\overrightarrow{A}\) der Ortsvektor eines Aufpunkts (Stützvektor) und \(\overrightarrow{u}\) ein Richtungsvektor der Gerade \(g\).

Gleichung einer Strecke \([AB]\) in Parameterform:

\[\overrightarrow{X} = \overrightarrow{A} + \lambda \cdot \overrightarrow{AB}, \; \textcolor{#cc071e}{\lambda \in [0;1]} \]

Da das Skalarprodukt der Vektoren null ist (Bedingung), formuliert \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}}\) die Koordinaten des Lotfußpunkts von \(C\) auf die Gerade \(AB\) als einen beliebigen Punkt auf der Gerade \(AB\) in Abhängigkeit des Parameters \(\lambda\). Dem Ergebnis der Rechnung ist zu entnehmen, dass \(\textcolor{#0087c1}{S}\) der zu bestimmende Lotfußpunkt ist.

Die Lösung der Gleichung liefert mit \(\textcolor{#e9b509}{\lambda = 0{,}8}\) genau den Wert des Parameters, der eingesetzt in die Gleichung der Gerade \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}\) die Koordinaten des Lotfußpunkts \(\textcolor{#0087c1}{S}\) ergibt.

\(\textcolor{#0087c1}{S} \in \textcolor{#cc071e}{AB} \colon \textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{S}} = \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 6 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}} \textcolor{#cc071e}{+} \textcolor{#e9b509}{0{,}8} \textcolor{#cc071e}{\cdot} \textcolor{#cc071e}{\begin{pmatrix} 6 \\ -3 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}} = \textcolor{#0087c1}{\begin{pmatrix} 4{,}8\\3{,}6\\0 \end{pmatrix}}\) \(\Rightarrow \;\textcolor{#0087c1}{S(4{,}8|3{,}6|0)}\)

Der erste Teil der Rechnung formuliert also einen typischen Lösungsansatz, um mithilfe des Skalarprodukts zweier zueinander senkrechter Vektoren, den Lotfußpunkt des Lotes eines Punktes auf eine Gerade zu bestimmen.

(vgl. Abiturskript - 2.4.1 Abstand Punkt - Gerade und 2.6.2 Spiegelung eines Punktes an einer Gerade )

Zweiter Teil der Rechnung

Die Vektoraddition \(\overrightarrow{T} = \textcolor{#0087c1}{\overrightarrow{S}} + \textcolor{#0087c1}{\vert \overrightarrow{CS} \vert} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) erzeugt einen Punkt \(T\), der senkrecht über \(S\) liegt und von \(S\) den gleichen Abstand hat wie der Punkt \(C\). Denn \(\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) ist ein Einheitsvektor der Länge 1, der in positive \(x_3\)-Richtung zeigt und der Faktor \(\textcolor{#0087c1}{\vert \overrightarrow{CS} \vert}\) verlängert diesen entsprechend.

Da \(\overrightarrow{CS}\) in der \(x_1x_2\)-Ebene liegt und \(\overrightarrow{ST} = \textcolor{#0087c1}{\vert \overrightarrow{CS} \vert} \cdot \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) in positive \(x_3\)-Richtung zeigt, sind die beiden Vektoren zueinander senkrecht.

Somit ist \(T\) derjenige Punkt, der aus Punkt \(C\) durch Drehung um 90° um die Gerade \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}\) entsteht.

Entstehung des Punktes \(T\) aus dem Punkt \(D\) durch Drehung um 90° um die Gerade \(\textcolor{#cc071e}{AB}\)